Travel Journal 1955-1965: Stories from a Maltese Sailor in the British Merchant Navy

Niamh Dann- Guest Writer

My Grandad, Saviour Borg, was a Maltese Merchant Sailor working in the British Navy between 1955 and 1965. My memories of him are filled with stories from countries all around the world. He would talk about them to anyone who would listen. My younger self, however, was mainly disinterested by these stories.

After his death in 2016, he gave to my brother a travel journal; one that he’d written in the last years of his life. Having read it completely only during quarantine, I was amazed and bewildered by the fascinating experiences my Grandad had travelling the world. His journal gets straight to the point on time, places and people. He talks little about his feelings and never goes into great detail. It is instead a short revival of what he called ‘the good old days’ of his life.

What I doubt Saviour would have realised is the historical importance of his travel journal and what it means for the history of politically categorised ‘non-white foreign’ participation in the British Merchant Navy. Maltese sailors, specifically, were extremely influential on the successfulness of the Navy. This journal, therefore, also brings light to a history that has been relatively lost and forgotten.

The Traveller – Seeing the World

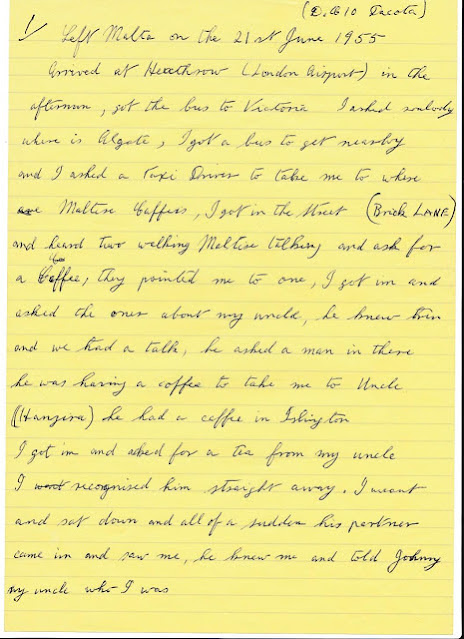

Leaving Malta and coming to London in 1955 was the first time Saviour Borg had left his home Island of Malta. Travelling seemed to be relatively easy. He asked for directions a lot and was lucky enough to have relatives in the country. For a foreigner travelling alone, this first experience away from his normality seemed to have filled him with a desire to see more. Once he revealed to his Uncle, Hanjira (a nickname: it means pig in Maltese), that he wished to join the Merchant Navy, his Uncle wasted no time in calling a friend who owned a boarding house in Cardiff and made this a reality for him.

This decision seems to come relatively out of nowhere. Saviour, however, would have been influenced by the British Navy his whole life. Malta was one of Britain’s principal navy bases (they were still owned by Britain at this time; not declaring independence until 1964.) They were also home to the Royal Navy’s Mediterranean Fleet. Employment with the Merchant Navy was common. Between 1956 and 1960, around 932 Maltese sailors were engaged in service. This might not seem like a lot, but with a population of only 10,986 men aged 20-24 living in Malta in 1955, almost 1,000 of them working in the Merchant Navy is an enormous number.

The British Merchant Navy covers the commercial interests of the UK ships and their crews. This includes trading and transport all around the world. The Merchant Navy had grown from the expansion of the British Empire with its trading of products from possessions in India and the Far East in the nineteenth century.

Amongst stories of volcano eruptions and the various histories of countries, he lists his ships and recounts his experiences on them. His first ship was the S.S Avon (in brackets it says ‘Panarain Flag’). He worked the kitchens as a wash boy and prepared the food for the crew. His first destinations in this ship were Toronto, Montreal and Quebec City, Canada. The ship was unfortunately scrapped. Employment for the Maltese on these ships varied. Saviour had one of the most common jobs for Maltese sailors. They tended to be below board in the engine rooms and kitchens, away from the glamour of top deck. They were the men that kept them afloat; a fundamental part of the workings of the ship.

His second ship was the S.S Scottish Monarch. Seeing America, Japan, British Columbia and Canada in only the first few months. The first time he jumped ship was in Vancouver, Canada. To someone who never knew him, the idea of a sailor jumping ship and living in a country illegally, crossing state borders and sleeping rough, might seem terrible. To Saviour, however, this would have been a source of comedy for him. He was the type of man where jumping ship was a way to not only investigate a country as a lonely traveller, but also a source of amusement in knowing that everyone from the ship would be wondering where he was. He crossed the border into America, spent the night in someone’s outside toilet in a small town called ‘Blain’ and attempted to get a train from Seattle to San Francisco. Here, he was caught by police looking for ‘border crossers.’ They caught 6 to 8 of them. The Emigration Department of Justice flew him to Honolulu, Hawaii where he was eventually reunited with the S.S Scottish Monarch.

The next time he jumped ship was in 1956, in Sydney, Australia.

He stayed in Australia for 19 months, mainly making money through gambling. He bought cars and motorbikes and even had his own flat. Australia was the ultimate adventure and he seemed to make a good life for himself there. But, after becoming bored by the heat and vastness of the country, he went to emigration and handed himself in.

This part of the journal was fascinating for me to read. I remember that he talked incessantly about Australia. Everything that had ever happened or anything he had ever experienced, always occurred when he was in this country living as an illegal immigrant and deserter. It was and still is a run-on-joke in our family that anything you can’t prove, happened in Australia.

Saviour’s disregard for the rules and his duty as a Merchant Sailor for the British seems almost laughable. He was a sailor because he had a desire to see the world, not to serve the British. Indeed, it seems that most Maltese sailors had similar notions. Between 1956 and 1960, 801 Maltese Merchant Sailors were discharged. This could suggest that Saviour was one of the lucky ones. Despite deserting twice, he seemed to have several working lives.

His third ship was ‘The Egyptian Prince’. On this ship he travelled through Europe: The Netherlands, Belgium, France, Germany, Denmark, Norway, Sweden and Finland.

His fourth ship was the S.S Empress of France. Around this time, he met my Nan, Patricia, and so travelled less; taking ships that would travel for no more than 4 months. He started reducing his number to only 3 or 4 trips a year. As his personal life began taking over, his travels became less frequent. He married Patricia in 1963. By 1965, ‘the good old days were over.’ Container ships and bigger passenger ships were replacing the Merchant Steam Ships. Work was lost to thousands of dockers.

He explains that he “travelled the world for nothing and [was] payed for it. I was one of the lucky ones. I came home on my last ship and the Victoria Docks were practically empty. So, I said to myself goodbye to ships and sleep on land.”

Despite maintaining its dominant position since the seventeenth century, the Merchant Navy began to decline with the deterioration of the British Empire, the rise of the use of the flag of convenience (registering a ship in a ship register of a country rather than that of the ship’s owner) and foreign competition. In 1939 the British Merchant Navy was the largest in the world with 33% of total tonnage. This number decreased throughout the rest of the twentieth century. By 2012, this number was 3%.

After his travels were over, he settled in with Patricia and got himself a job at Whitbread Brewery. My Mum was born four years later. By this time, he was working as a driver for dustcarts in the North of London. He remained in this job until he retired in his 50’s.

The time he calls ‘the good old days’ were the best years of his life. Travelling the world allowed him to experience things he wouldn’t have anywhere else. He lived the life of a free man and experienced little consequence, even for his illegal wrongdoings. Reading the journal seems like experiencing a different world at a different time. However, this was of his own creation. He made his world one of adventure and excitement. Perhaps this shows how important it is to take chances in life and take full advantage of the opportunities that come your way. From a man who in older age lived the simplest of lives in front of his television for the last thirty years of his life, perhaps it’s also important not to burn your adventurous side out too soon.

Favourite Experiences in the journal

1. Escaping border patrol in America

After jumping ship in British Colombia, he managed to cross the border into Canada. After spending the night in an outside toilet and crossing under a bridge to get to the American border, Saviour managed to avoid the searchlights by laying down on the ground and crawling past the border patrol. He didn’t last long in America though. He was caught by the police attempting to get a train from Seattle to San Francisco.

2. Arriving in communist China

When his ship, the S.S Scottish Monarch arrived in Shanghai, Saviour found himself surrounded by high electric steel walls and plenty of police and army personnel. Saviour was the only one to step on the ground to load some vegetable stores. He was ‘surrounded by stary eyes.’

3. Being an illegal deserter in Australia for 19 months

He must have really liked the look of Australia when he arrived in 1957 because he jumped ship and lived there for 19 months. He made money through gambling and bought and resold cars and motorbikes. He dressed well, ate well, went horse racing and hunted rabbits and wild pigs. He describes his time in Australia as ‘living a life of Riley.’

4. Buying his way onto a ship

After a Merchant Navy Strike in 1963, Saviour needed to find work. He explains that he knew a guy who ‘for money would sell his own mother.’ The guy offered Saviour a place on a ship for £5. Saviour replied, “get me one in a week and I’ll give you £10”. Three days after, he was on the S.S Empress of France.

Bibliography

Dr Carmel Vassallo, ‘Sailing Under the Red Duster: Maltese Merchant Seafarers in the Twentieth Century’, The Mariner’s Mirror, 94:4, (2008).

Population Pyramid, ‘Population Pyramids of the World 1950 to 2100’, Malta, https://www.populationpyramid.net/malta/1955/

Hope, Ronald, A New History of British Shipping, London: John Murray, (1990).

Comments

Post a Comment